|

|

ADVERTISEMENT

Buy Your own advertising

spaces!

.

Download Adobe Acrobat Reader to open [PDF] files.

Recent Visitors

Expo 2010 isn't supposed to be a circus act

2010. 15 January

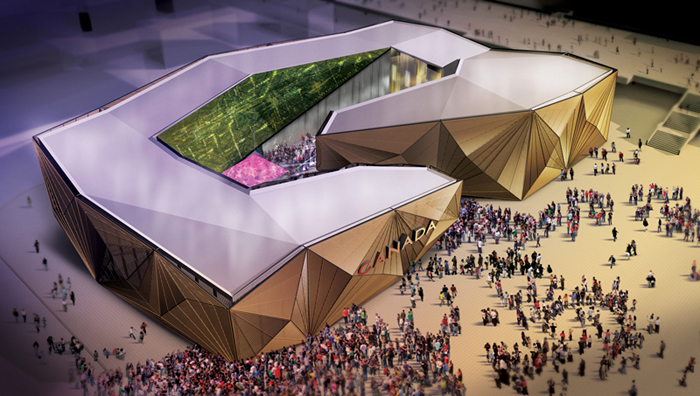

The Canadian pavilion for World Expo 2010 in Shanghai (artist’s rendering), budget, about $58-million: Many other countries launched high-profile competitions to pick their pavilion’s designer.

The Canadian pavilion for World Expo 2010 in Shanghai (artist’s rendering), budget, about $58-million: Many other countries launched high-profile competitions to pick their pavilion’s designer.

by Lisa Rochon

It was shabby of the Harper government to choose Cirque du Soleil's one-stop showmanship over a landmark Canadian architectural moment

(theglobeandmail.com)

Let's say you're the head of a state and you've been given an enormous, prestigious site to advertise the creative brains of your country to about 70 million people touring through a world fair. You're thinking, okay, showcase imagination, no need to translate. Straight away, you're calling up compelling talent – cool video artists and aboriginal performers – and figuring out how to seal lucrative business deals in your fancy VIP lounge. Turns out your pavilion, at 6,000 square metres or almost as large as four National Hockey League rinks, is one of the biggest among the 43 nations and organizations that are building stand-alone pavilions.

Other nations launch architecture competitions and unveil their designs with much fanfare in what has become a kind of Olympics of architecture and art. Not you, Mr. Canada. You farm out the commission for the Canadian Pavilion at World Expo 2010 in Shanghai to a circus corporation. Oh, Canada. Hewer of wood and drawer of water. You dumb cluck. You allow a monumental nation-branding building to be conceived without an architect.

There are 8,000 licensed architects in Canada. But, don't expect to find a single architecture firm's name attached to the Canadian Pavilion in Shanghai. That's because an in-house “creator” at the Cirque du Soleil has authored the concept. Think about it and laugh at the sad clown act we're offering at the biggest exposition ever staged in the world.

Not surprisingly, what has been conjured is a made-in-Canada bowl of architectural gruel. The slanted roof and triangulated exterior skin are meant to give the building that edgy, scary Daniel Libeskind kind of feel. But, so as not to offend, the exterior decorative cladding in British Columbia red cedar will surely warm the hearts of the five million visitors expected to visit the Canadian pavilion from May until October. The pavilion's creator, Johnny Boivin of the Cirque du Soleil, conceptualized the building with a 3-D model and then “a little maquette.” Boivin, a well-meaning guy who holds a masters degree in philosophy, describes the motivation for the so-called architectural form: “All the building is clad in red cedar, a Canadian wood. Natural resources are very precious, so I work with wood as if it is stone or diamond. The shape resembles the angles of stone.”

Our federal Department of Canadian Heritage handed the entire project – not just the building, but the conceptual design for the public plaza, the lighting and sculpture, as well as the curating of the performances and exhibition – to the Cirque. The important Montreal firm Saia Barbarese Topouzanov Architectes was hired by Boivin to help finesse his conceptual design for the pavilion, but only the Cirque gets credit on the publicly released architecture renderings. (A contract of confidentiality stipulates the architects can only speak publicly about the design after permission is granted by the Cirque.) In this bizarre scenario, architects play the role of silent, invisible technicians toiling anonymously in some back office.

A fully engaged architect might have referred in the design to the pavilion site located within an old industrial district on the Pudong side of the Huangpu River. But urban context matters not at all to creators of theatrics. Treating space as a stage set – one that comes with a VIP lounge affording views on the interior courtyard – is how the Cirque approaches architecture. That's okay when you're designing tents, but it's hardly the way to communicate deep architectural insight.

There's the predictable quotient of greenwashing in the pavilion. The interior features a living green wall, actually a map of Shanghai – constructed of local Chinese plants. The interior cladding of stainless steel and the red cedar is to be recycled once the temporary pavilion comes down, promises Charles Chebl, director of the project for the pavilion builder, the Montreal-based engineering and construction firm SNC-Lavalin. Another Montreal firm, ABCP Architectes, was hired as a subcontractor to SNC-Lavalin to do the working drawings for the pavilion. So now we can still sport the Canadian flag on our backpacks and feel proud.

The sad truth, though, is that there's nothing innovative or truly inspiring – just a $28-million building (the total Canadian budget for the six-month event is $58-million) amounting to a patchwork of visuals gleaned from the world's design magazines. For this, we have the visionaries at Canadian Heritage to thank. Next to the sophisticated understanding of architecture in other countries, Canada's process is remarkably, memorably shabby. If there were any doubts in the minds of Prime Minister Stephen Harper and his minions around the significant visibility of architecture at world expositions, they might have flipped through the pages of history – there are plenty of pictures – pertaining to the Great London Exhibition of 1851, the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris and the 1939 and 1964 world's fairs in New York. They might have tuned in to the major design competitions sponsored by Denmark, Italy, Britain, Chile, Belgium, Poland and Austria to select architecture that addresses issues of volume, fluidity and fresh, innovative materials. Led by architect Giampaolo Imbrighi, the winner of a Europe-wide competition, the Italians will present a modular pavilion constructed of cutting-edge transparent concrete. Britain's Foster + Partners is designing the United Arab Emirates pavilion in the image of a sand dune. For the Danish pavilion, the red-hot architects BIG have innovated a mega loop that doubles as a road on which visitors can ride one of the 1,500 bikes available at the entrance. Inside, there's to be a large reflecting pool with fresh water from the recently cleaned Copenhagen harbour, and at the centre of the pool, the Little Mermaid, the iconic statue that will be moved – for the first time – temporarily to China for the world exposition. The architects are clearly named and linked with each of these world pavilions, not subsumed into a mega-corporation of circus production, as in the Canadian scenario. They're even allowed to speak. In the words of Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, principal of BIG Architects: “It is considerably more resource-efficient moving the Little Mermaid to China, than moving 1.3 billion Chinese to Copenhagen.”

How to explain the decision by the Department of Canadian Heritage to favour the makers of a great big circus over the great big talent of Canadian architects? I asked the question repeatedly, but apparently, we're to be satisfied with this e-mailed answer from Heritage: “The reputation and unique brand of Cirque du Soleil is well known and highly respected around the world – including in China. The Government of Canada entered into a collaborative arrangement with Cirque to develop the overall concept and design for the pavilion, create the public presentation program for visitors and manage Canada's cultural program at the Expo.”

Decision makers at Heritage need to get out from under the Big Top and breathe some fresh air. “I'm totally disappointed,” says Jon Hobbs, executive director of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. “Whoever initiated this didn't have a real understanding.” The insult deserves to be shared – by the Cirque du Soleil for its refusal to acknowledge creative authorship, and by its client, the Government of Canada, for failing to recognize the power of real architecture. What a juggling act. What a laugh.

Source: www.theglobeandmail.com